The law-making process can be understood in terms of four distinct stages:

It should be noted that the legislative process for private members’ bills and private bills differs from that for government bills. 1 This paper discusses the legislative process for government bills only.

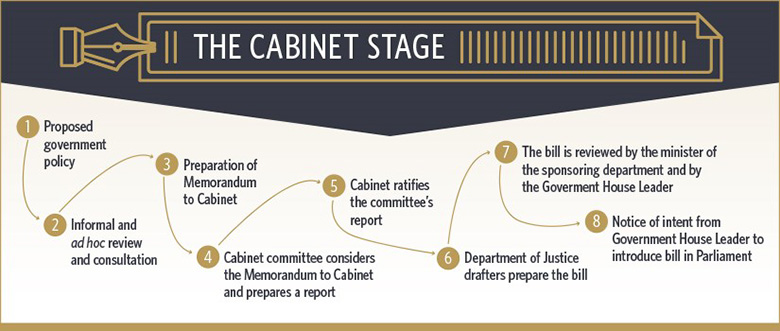

Figure 1 – Cabinet Stage

Source: Figure prepared by Library of Parliament.

The primary purpose of the Cabinet stage is to review and decide which measures the government wants to implement through legislation. Government policy – often announced in the Throne Speech, the budget, international or federal/provincial agreements, ministerial proposals and other sources – is the point of origin for most federal government legislation.

The appropriate federal departments review these sources to determine whether legislation is needed to implement a policy. If so, the relevant minister may, if he or she wishes, allow departmental officials to proceed with policy consultations. These consultations allow stakeholders, other departments, provincial governments and others to provide input into the legislation before it is drafted.

In light of these consultations, and contingent upon a decision being made to proceed with legislation to achieve the policy objectives, the sponsoring department prepares a Memorandum to Cabinet. 2 The Memorandum to Cabinet seeks policy approval and authorization for the Department of Justice to begin drafting the legislation. Also included in the memorandum are drafting instructions that describe the contents of the bill in a clear manner for legislative drafters at the Department of Justice.

Before completing the Memorandum to Cabinet, the sponsoring department hosts an interdepartmental consultation. After the affected departments and agencies are adequately consulted, the draft memorandum is revised, taking into account comments from other departments. Once finalized, it is submitted for approval to the appropriate Cabinet policy committee, which reviews the memorandum and prepares a report. For the policy to proceed, Cabinet as a whole must ratify the report of the policy committee.

Once Cabinet approves the Memorandum to Cabinet and the drafting instructions, the legislative drafters prepare a bill in both official languages. This is done in consultation with the sponsoring department and its legal services. The draft bill is reviewed and approved by the sponsoring minister and the government House leader, who ensure that it is consistent with past Cabinet decisions, as well as by the Minister of Justice, who ensures that the bill is consistent with the Canadian Bill of Rights and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. 3

The government House leader will then seek delegated authority from Cabinet to approve the bill for introduction in Parliament. The chamber in which the bill will be introduced and the timing of the introduction are determined by Cabinet on the advice of the government House leader and in consultation with the sponsoring minister. Typically, government bills are introduced in the House of Commons rather than in the Senate. Legislation that involves spending or taxation measures must be introduced in the House of Commons. 4

At this point, the bill is almost ready to be introduced in Parliament. 5 Bills that involve expenditure of public money require a royal recommendation 6 before they can be passed by the House of Commons. A royal recommendation is obtained from the Governor General or a deputy of the Governor General (a Supreme Court judge). In current practice, the royal recommendation for government bills is communicated to the House of Commons before the bill is introduced and is included on the Order Paper. After first reading, the recommendation is printed in the Journals and included in the first reading copy of the bill.

If the bill is to be introduced in the House of Commons, the government House leader must give the Clerk of the House of Commons advance notice; typically, the notice period is 48 hours. 7 The bill appears first on the Notice Paper 8 and is subsequently moved to the Order Paper 9 until its introduction by the appropriate minister.

If the bill is to be introduced in the Senate, no notice is required. 10

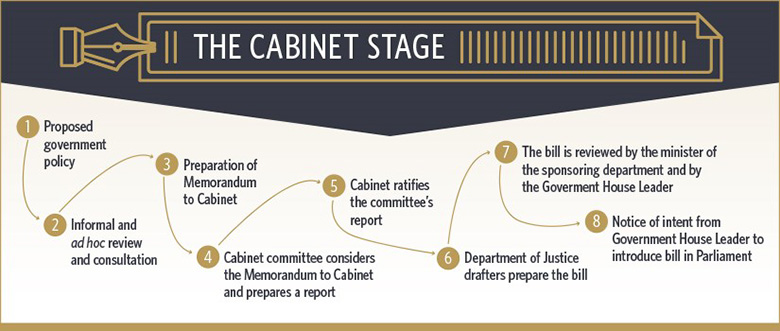

Figure 2 – Parliamentary Stage

Report stage 5. Third reading When the bill passes these five steps in the House of Commons or the Senate, it goes to the other chamber. When the bill passes these five steps in the second chamber, it is almost law. " />

Report stage 5. Third reading When the bill passes these five steps in the House of Commons or the Senate, it goes to the other chamber. When the bill passes these five steps in the second chamber, it is almost law. " />

Source: Source: Figure prepared by Library of Parliament.

The bill must pass through both houses of Parliament, beginning in the one in which it was introduced.

For government bills introduced in the House of Commons, the steps in each house are as described below. (The process is similar for government bills introduced in the Senate, but in this case, the process begins in the Senate.)

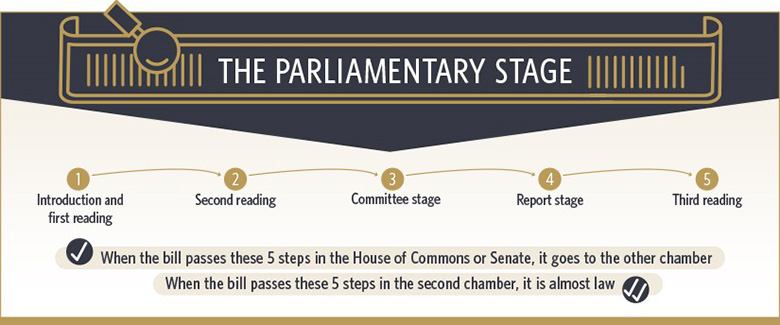

Figure 3 – Royal Assent and Coming-into-Force Stages

Source: Figure prepared by Library of Parliament.

When both the Senate and the House of Commons have passed a bill in the same form, the bill awaits Royal Assent. Royal Assent is the point at which a bill becomes an Act.

Traditionally, Royal Assent was granted only during a special ceremony in the Senate chamber involving the Governor General or a deputy of the Governor General (a Supreme Court judge), the Senate and the House of Commons.

In 2002, legislation was passed that permits Royal Assent to be signified by a written declaration, which can take place away from the Senate and House of Commons. The Royal Assent Act requires, however, that the traditional ceremony also be maintained. It is to be used at least twice in each calendar year, including for the first appropriation bill in each session. The Act also requires that the Speakers of both the House of Commons and the Senate be notified of the written declaration before a bill is deemed to have received Royal Assent.

Although a bill becomes an Act when it receives Royal Assent, the legislation is not automatically in effect. Acts come into force in various ways, and each Act must be examined to determine which commencement mechanism applies.

If an Act does not contain a provision specifying the date that it enters into force, the Interpretation Act states that the Act comes into force on the day it receives Royal Assent.

If the Act has sections providing for the coming into force of the Act, these provisions can take many forms, such as the following:

It is also possible for an Act to take a very long time to be proclaimed in force. In 2008, in response to the fact that some Acts that had been granted Royal Assent decades earlier had yet to be proclaimed in force by the Governor in Council, a Senate public bill was passed providing for the repeal, on 31 December of each year, of any legislation that has not come into force within 10 years of receiving Royal Assent. This Act, known as the Statutes Repeal Act, came into force in 2010.

When an Act comes into force, the transition from policy to enforceable law is complete.

† Papers in the Library of Parliament’s In Brief series are short briefings on current issues. At times, they may serve as overviews, referring readers to more substantive sources published on the same topic. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. [ Return to text ]

* A previous version of this paper was prepared by Megan Furi, formerly of the Library of Parliament, and by Peter Niemczak of the Library of Parliament. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament